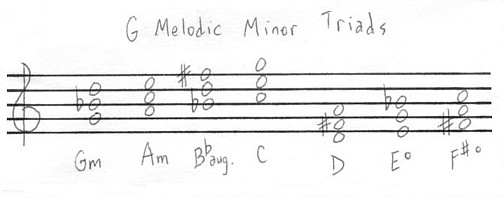

Triads:

i- ii-

bIII+ IV V

vi° vii°

Triads:

i- ii-

bIII+ IV V

vi° vii°

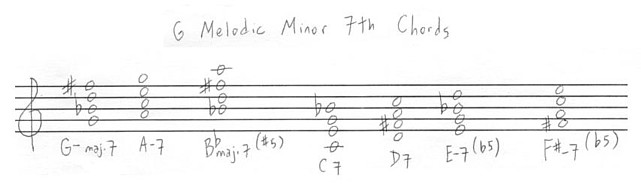

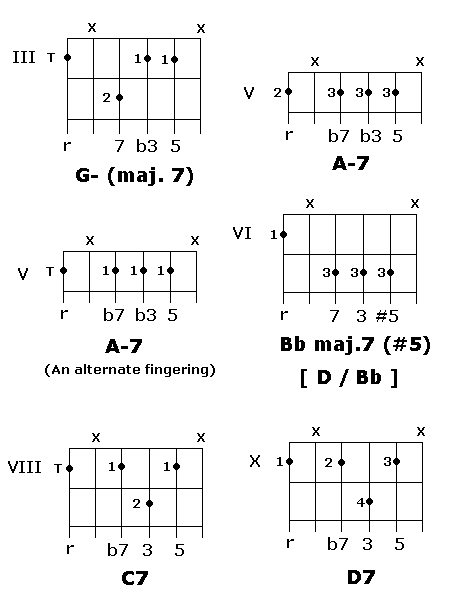

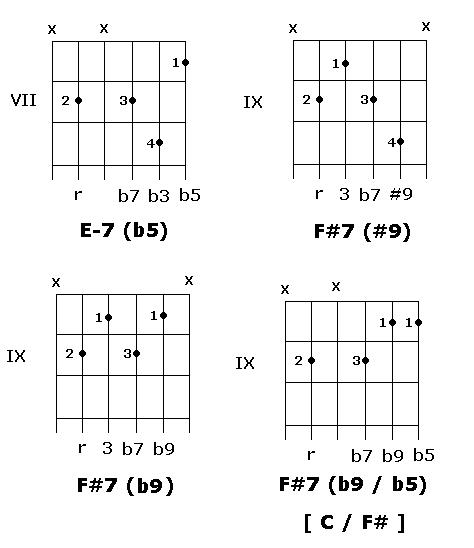

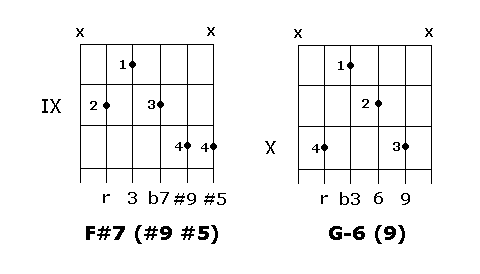

7th Chords:

i- (maj.7) ii-7

bIII maj.7 (#5) IV7 V7

vi-7 (b5) vii-7 (b5)

7th Chords:

i- (maj.7) ii-7

bIII maj.7 (#5) IV7 V7

vi-7 (b5) vii-7 (b5)

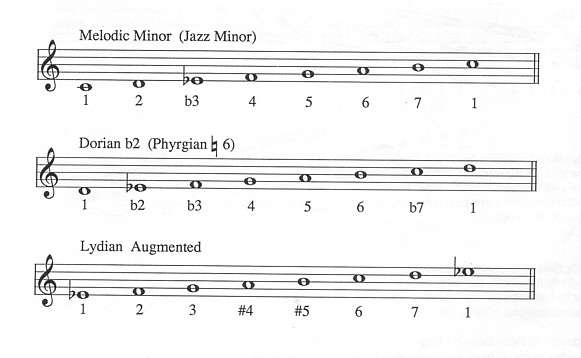

| Note Function: | R | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C Major Scale: | C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C |

| Note Function: | R | 2 | b3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C Melodic Minor Scale: | C | D | Eb | F | G | A | B | C |

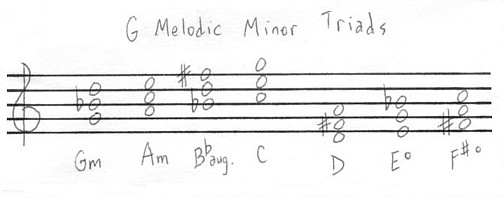

Triads:

i- ii-

bIII+ IV V

vi° vii°

Triads:

i- ii-

bIII+ IV V

vi° vii°

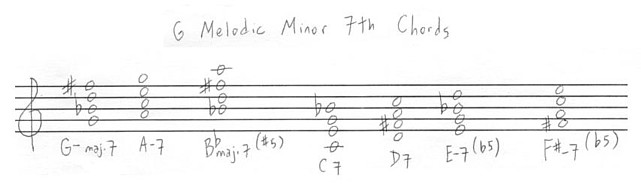

7th Chords:

i- (maj.7) ii-7

bIII maj.7 (#5) IV7 V7

vi-7 (b5) vii-7 (b5)

7th Chords:

i- (maj.7) ii-7

bIII maj.7 (#5) IV7 V7

vi-7 (b5) vii-7 (b5)

| Major Scale Triads: |

I | ii- | iii- | IV | V | vi- | vii° |

| Mel. Min. Scale Triads: |

i- | ii- | bIII+ | IV | V | vi° | vii° |

| Major Scale 7th Chords: |

I maj.7 | ii-7 | iii-7 | IV maj.7 | V7 | vi-7 | vii-7(b5) |

| Mel. Min. Scale 7th Chords: |

i- (maj.7) | ii-7 | bIII maj.7 (#5) | IV7 | V7 | vi-7 (b5) | vii-7(b5) |

| Major Scale 7th Chords: |

I maj.7 | ii-7 | iii-7 | IV maj.7 | V7 | vi-7 | vii-7(b5) |

| Mel. Min. Scale 7th Chords: |

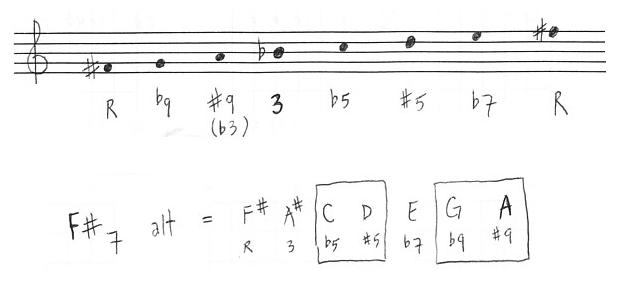

i- (maj.7) | ii-7 | bIII maj.7 (#5) | IV7 | V7 | vi-7 (b5) | VII7 alt |

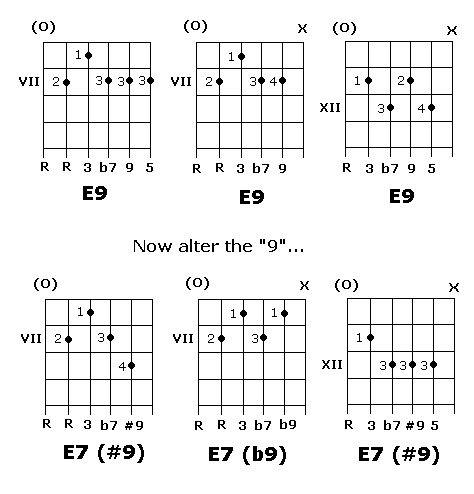

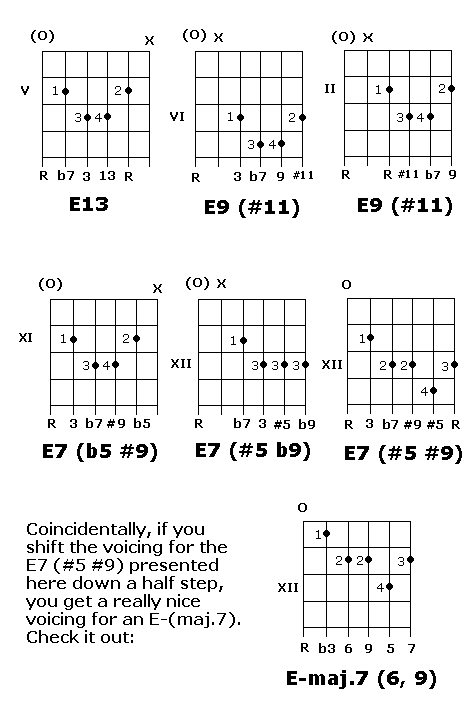

| Note Function: | R | 3 | 5 | b7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E7 chord: | E | G# | B | D |

| Note Function Against E7: | b3 or #9 | b5 or #11 | #5 or b13 | b7 | b9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gm Pentatonic: | G | Bb | C | D | F |